We asked this question directly from the source. HR professionals, managers, and senior leaders from 63 medium-sized and large organizations across multiple industries responded to our questionnaire. Our goal was to move beyond policy statements and diversity slogans and understand what kinds of neuro-inclusive practices are actually available to employees in everyday working life.

The answers reveal a familiar pattern. There is goodwill. There are individual accommodations. There are also some genuinely strong practices. But overall, neuro-inclusion remains fragmented and far too often dependent on individual managers—or on employees having the energy, confidence, and psychological safety to ask for support.

What companies say they offer

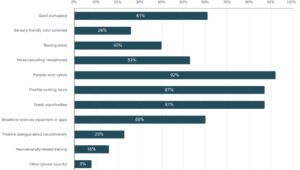

The below chart summarizes how much of prenamed neuro-friendly practices organizations report having in place.

The most widely available supports are flexibility-related to remote work options, flexible working hours and break opportunities during the workday. Flexibility is often the single most impactful factor for neurodivergent employees’ wellbeing and performance. However, flexibility alone does not yet equal neuro-inclusion.

More concrete environmental or structural supports appear far less consistently. These include quiet workspaces, resting areas, and sensory-friendly color schemes. Naturally, these types of accommodations are partly dependent on industry, role, and physical environment, and are not feasible in all jobs.

What is particularly interesting, however, is that the measures that would be applicable across all industries, roles, and work environments received the lowest levels of adoption. These were positive dialogues about neurodiversity and neurodiversity-related training.

In other words, companies are relatively good at offering general flexibility, but much weaker when it comes to intentional neuro-inclusive design, leadership capability, and shared understanding.

When we, instead, asked in an open-ended question, “What types of support are available for neurodivergent employees (e.g. ADHD, autism spectrum, dyslexia)?”, we reached a better understanding of the maturity the companies were in their neuroinclusive practices and forms of support. We saw three emerging categories:

Category 1: “Nothing, unless someone asks”

Most responses fell into this category: They had no formal support model, but handled indivual’s needs case by case if raised.

Example responses included:

There are no specific support measures unless the issue is explicitly raised with occupational health.

No official support structures exist. Everything is handled individually if needed.

Not officially anything, but if someone brought this up, we could probably think about suitable support.

None at all. Results are measured and you just have to cope.

This reactive model places most of the responsibility on the individual employee to recognize own needs, disclose them, trust that disclosure is safe, and then negotiate accommodations. For many neurodivergent people, this is too high a bar.

Category 2: Reasonable but indirect measures

The second largest group fell in the second category that consists of measures that are genuinely good and often extend beyond the average, such as extensive occupational health services, including preventative mental health and wellbeing support. However, these measures are not always explicitly directed toward neuro-inclusion, but are generic in nature. This category also includes quiet rooms, private offices, flexible location models, and different types of workspaces that employees can choose from.

One of the most comprehensive responses stated:

All reasonable measures must be taken to ensure that practices, ways of working and cultures do not discriminate against neurodivergent people… Support needs must be identified and implemented based on individual assessment—not assumptions or stereotypes.

Another respondent highlighted practical adjustments to everyday work:

Instructions are provided as videos as well as in writing. We avoid long written guidelines and use checklists for recurring tasks. Employees are encouraged to develop different ways of working.

These examples show that neuro-inclusion is quite easily achievable when it is taken into careful consideration.

Category 3: Practices that hinder inclusion

More concerning were some responses that revealed not a lack of support, but organizational practices and attitudes that actively undermine inclusion. Examples included:

I don’t recognize any support—more a ‘reluctant’ attitude toward employee ‘demands’.

The organization is very process-driven. There is no room for differences; everyone is standardized into the same ‘machine parts’.

I’m not aware of anything, but I feel like I should know in my role.

Perhaps most telling were comments in which leaders themselves admitted they did not know what support existed, or whether any existed at all. This lack of visibility alone makes support inaccessible, even when it technically exists.

Where this leaves us

On paper, many companies appear to be doing well: flexible work arrangements, occupational health services, and some quiet spaces. But on closer inspection, neuro-inclusion is still rarely intentional, systematic, or clearly communicated.

Support remains undocumented, manager-dependent, available only after problems escalate, and invisible unless you already know where to look. As one respondent put it:

There is a lot of information and materials—but it’s scattered and not communicated externally or clearly internally.

As a result, neurodiversity is still largely treated as an exception rather than a normal part of workforce diversity. Most organizations rely on general flexibility and individual resilience instead of building environments, cultures, and leadership capabilities that truly support different neurotypes.

The good news is that the building blocks already exist in many organizations. What is missing is structure, leadership commitment, and the courage to move from ‘we can discuss this if someone asks’ to ‘this is how we work here.’

Author: Heini Pensar